"No man can be a genius in slapshoes and a flat hat." -Buster Keaton -

"No man can be a genius in slapshoes and a flat hat." -Buster Keaton -

Buster Keaton was one of the greatest comedic actors and filmmakers during the silent film era of the 1920s. Known for his trademark deadpan expression and incredible physical comedy stunts, Keaton created some of the most iconic and hilarious silent films of all time. In this blog post, I’ll provide an overview of Keaton’s life and career, from his early days in vaudeville to his legendary run of silent feature films in the 1920s.

We’ll explore his most famous gags and stunts, his pioneering film techniques, and the lasting legacy he left on comedy and cinema. Though he faced personal struggles later in life, Keaton’s ingenious comedic talents cemented him as a true legend of the silent screen. So get ready to learn all about the life and works of the great “Stone Face” himself, Buster Keaton.

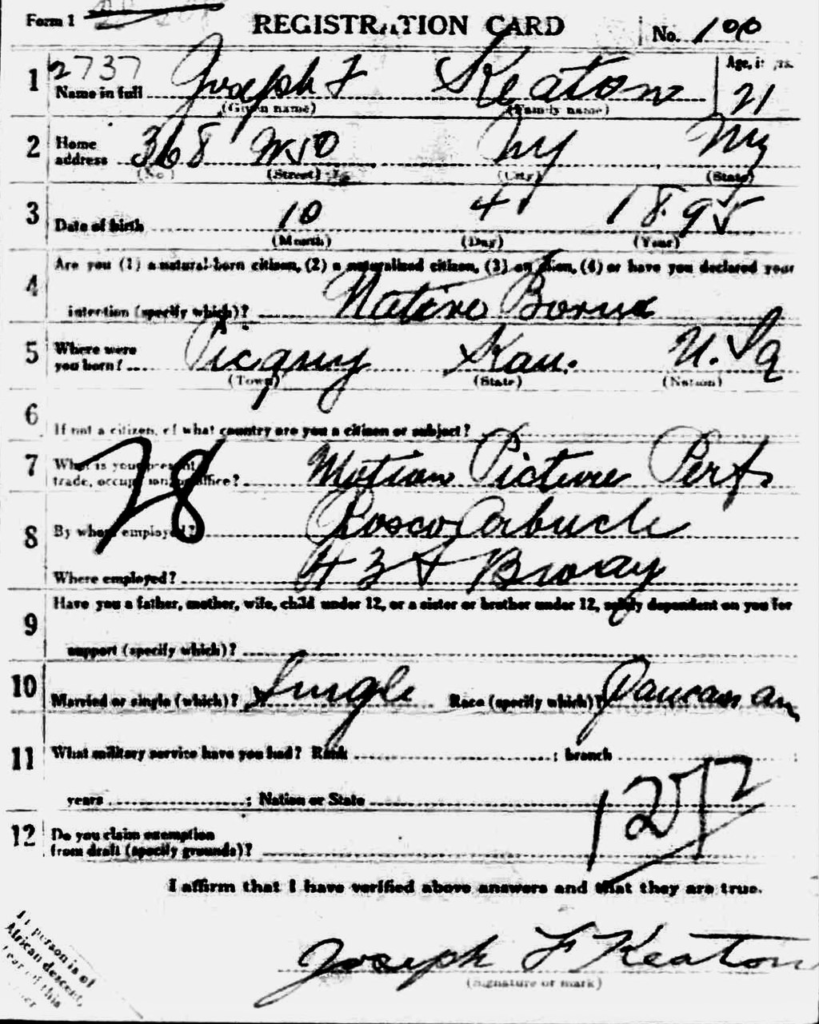

Buster Keaton was born into a family deeply rooted in vaudeville, in the modest town of Piqua, Kansas. His mother, Myra Keaton (née Cutler), happened to be visiting Piqua when he was born. He was given the name Joseph, carrying on a tradition from his father’s side, where he was the sixth in line to bear the name Joseph Keaton. The name Frank was added in honor of his maternal grandfather, who initially disapproved of his parents’ union.

His father, Joseph Hallie “Joe” Keaton, was the proprietor of a traveling show called the Mohawk Indian Medicine Company. This unique troupe not only performed on stage but also peddled patent medicine as part of their act. One widely circulated, albeit possibly apocryphal, story recounts how Keaton acquired the nickname “Buster” at a mere 18 months of age. It’s said that after surviving a perilous fall down a long flight of stairs unscathed, an actor friend named George Pardey exclaimed, “Gee whiz, he’s a regular buster!” Consequently, Keaton’s father began affectionately referring to him as Buster, a nickname that would stay with him throughout his life. Keaton himself recounted this story over the years, including during a 1964 interview with the CBC’s Telescope. In his retelling, he adjusted the age to six months and attributed the nickname to none other than Harry Houdini, although his family didn’t meet Houdini until a later time.

At the tender age of three, Keaton made his foray into showbiz by joining his parents in their act, known as The Three Keatons. His debut on stage took place in 1899 in Wilmington, Delaware, and the act primarily featured comedic sketches. During these performances, Myra played the saxophone off to the side, while Joe and Keaton took center stage. Young Buster’s role often involved taunting his father by deliberately disobeying him, prompting Joe to respond with humorous physical antics that sometimes involved tossing Buster around. To protect the young performer during these tosses, a suitcase handle was sewn into his clothing. The act continued to evolve as Keaton learned the art of executing safe trick falls, minimizing the risk of injuries during these slapstick interactions. Remarkably, despite the physicality of the act, Keaton rarely suffered any injuries or bruises. However, the knockabout nature of their comedy led to occasional accusations of child abuse and even arrests. Keaton, though, always managed to prove that he remained unharmed after these antics. He eventually became known as “The Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged,” and their act earned the moniker “The Roughest Act That Was Ever in the History of the Stage.”

Keaton would later emphasize that he was never hurt by his father’s actions, explaining that the falls and physical comedy were executed with precise technical expertise. In a 1914 interview with the Detroit News, he disclosed the secret behind their act: landing limp and using a foot or hand to break the fall. He described it as a skill he acquired from starting at such a young age, enabling him to land safely even in seemingly perilous situations. Imitators of their act, he claimed, failed to endure the treatment because they couldn’t master this crucial technique.

Keaton revealed that he enjoyed the act so much that he occasionally found himself laughing as his father tossed him around the stage. However, he noticed that his laughter diminished the audience’s response, prompting him to adopt the stoic, deadpan expression he would become famous for in his future performances.

Their act occasionally ran afoul of laws prohibiting child performers in vaudeville, and at one point in New York, Keaton was briefly enrolled in school while continuing to perform. His formal education was limited, and he learned to read and write later in life, primarily through his mother’s teachings. By the age of 21, the family act faced a considerable threat due to his father’s struggle with alcoholism, prompting Keaton and his mother, Myra, to depart for New York. In the bustling city, Keaton’s career rapidly transitioned from vaudeville to the world of film.

Keaton’s journey led him to serve in World War I with the American Expeditionary Forces in France, as part of the United States Army’s 40th Infantry Division. Remarkably, his unit remained intact and wasn’t disbanded to provide replacements, which was a fate that befell some other late-arriving divisions. During his service, Keaton developed an ear infection that left him with permanent hearing impairment, a consequence of his time in uniform.

Buster Keaton entered into matrimony with Natalie Talmadge on May 31, 1921, at Norma Talmadge’s residence in Bayside, Queens. They had two sons: Joseph, known as James (June 2, 1922 – February 14, 2007), and Robert (February 3, 1924 – July 19, 2009). Unfortunately, their marital bliss began to dwindle after Robert’s birth. Disagreements surfaced, leading to a separate bedroom arrangement and Keaton’s involvement with actresses Dorothy Sebastian and Kathleen Key.

The couple’s differing lifestyles exacerbated their issues. Keaton had constructed a cozy cottage-like home as a surprise gift for his bride, but it was met with disappointment by Natalie, who desired a grander residence. Consequently, he sold the cottage to MGM executive Eddie Mannix and commissioned Gene Verge Sr. to build a sprawling 10,000-square-foot estate in Beverly Hills for $300,000, later owned by James Mason and Cary Grant.

Despite attempts at reconciliation, divorce became inevitable in 1932, and Natalie changed their sons’ surname to “Talmadge.” Eventually, the boys, Robert and Joseph, made the name change permanent in 1942.

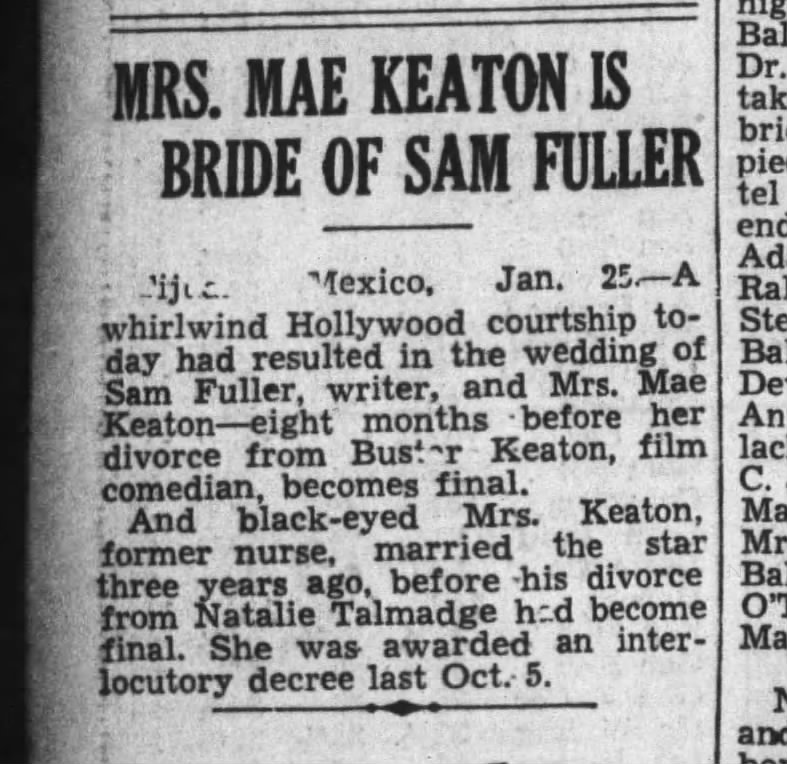

The failure of his marriage and the loss of creative independence led Keaton down a path of alcoholism. He spent a brief period in a mental health facility and employed escape techniques learned from Harry Houdini to break free from a straitjacket. In 1933, during an alcoholic episode, he wed his nurse, Mae Scriven, though he claimed to have no memory of the event. The marriage ended in divorce in 1936, at a significant financial cost to Keaton.

After undergoing aversion therapy, Keaton abstained from alcohol for five years. On May 29, 1940, he embarked on a new chapter, marrying Eleanor Norris, who was 23 years his junior. Eleanor played a pivotal role in revitalizing his life and career. Their union endured until Keaton’s passing. Between 1947 and 1954, the couple entertained audiences as a double act at the Cirque Medrano in Paris. Eleanor became so familiar with his routines that she often joined him in television revivals.

Buster Keaton’s early years were spent amidst the vibrant atmosphere of vaudeville. From 1908 to 1916, he found himself at the ‘Actor’s Colony’ in the Bluffton neighborhood of Muskegon, alongside other illustrious vaudevillians.

In February 1917, a significant turning point occurred when he crossed paths with Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle at the Talmadge Studios in New York City. At that time, Arbuckle was under contract with Joseph M. Schenck. Interestingly, both Keaton and his father, Joe Keaton, harbored reservations about the film industry. However, Keaton’s entry into the world of cinema unfolded almost serendipitously. During his initial meeting with Arbuckle, Keaton was unexpectedly invited to join in and commence acting. To everyone’s astonishment, Keaton displayed a remarkable aptitude for film acting in his very first appearance, which happened to be in “The Butcher Boy.” His performance was so impressive that he secured a job on the spot. After the day’s shoot, he even requested to borrow a camera to explore its workings. He diligently disassembled and reassembled the camera in his hotel room overnight.

In subsequent years, Keaton’s talents flourished, and he assumed the role of Arbuckle’s second director and oversaw the entire gag department. Together, they created 14 Arbuckle shorts, with the collaboration extending into 1920. These films enjoyed popularity, and contrary to Keaton’s later reputation as “The Great Stone Face,” he frequently displayed smiles and even laughter in these productions. The friendship between Keaton and Arbuckle deepened, and Keaton, along with Charlie Chaplin, stood by Arbuckle’s side during the tumultuous accusations surrounding actress Virginia Rappe’s death. Eventually, Arbuckle was acquitted, with a jury apology for the ordeal he endured.

In 1920, a significant milestone was reached with the release of “The Saphead,” where Keaton landed his first starring role in a full-length feature film. This cinematic endeavor was based on the successful play “The New Henrietta,” which had already been adapted into a film titled “The Lamb,” with Douglas Fairbanks taking the lead role. Fairbanks himself recommended Keaton for the role when it was decided to create a comedic version of the film five years later.

Following the fruitful collaboration with Arbuckle, Schenck granted Keaton his production unit, aptly named Buster Keaton Productions. Under this banner, Keaton crafted a series of 19 two-reel comedies, including classics like “One Week” (1920), “The Playhouse” (1921), “Cops” (1922), and “The Electric House” (1922).

(Image Source: Pintrest)

As the creative force behind these productions, Keaton frequently conceived ingenious gags himself. Fellow comedy director Leo McCarey humorously noted the futility of trying to pilfer Keaton’s talented gagmen, as Keaton generated his best gags independently. Some of his more daring ideas required perilous stunts, performed by Keaton with incredible physical risk.

In a famous incident during the filming of “Sherlock Jr.,” Keaton unknowingly broke his neck when doused by a torrent of water from a water tower. However, he remained blissfully unaware of this injury for years. Another unforgettable scene, this time in “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” demanded Keaton to stand immobile beneath the facade of a two-story building that collapsed around him. Keaton’s character miraculously emerged unharmed, thanks to a solitary open window, making for one of the most iconic moments in his career.

Apart from “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” (1928), Keaton’s enduring feature-length films include “Our Hospitality” (1923), “The Navigator” (1924), “Sherlock Jr.” (1924), “Seven Chances” (1925), “The Cameraman” (1928), and “The General” (1926). “The General,” set against the backdrop of the American Civil War, combined physical comedy with Keaton’s fascination for trains, resulting in an epic locomotive chase. Although it is now regarded as one of Keaton’s greatest accomplishments, contemporary reviews of the film were mixed. Some viewers found it too dramatic for a comedy, while others questioned the decision to create a comedic film about the Civil War, even though acknowledging it contained a “few laughs.”

“The General” was a costly venture, especially the climactic scene featuring a locomotive crashing through a burning bridge, which became the most expensive single shot in silent-film history. As a consequence, Keaton lost some creative control, with United Artists, his distributor, insisting on a production manager to supervise expenses and influence certain aspects of the storyline. Keaton endured these changes for two more feature films before transitioning from his independent setup to joining Hollywood’s largest studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). This marked a shift in his career trajectory, coinciding with the advent of sound films, personal challenges, and a decline in his early sound-era career.

Buster Keaton’s final trio of feature films had been produced and released independently, giving him creative control, but they fell short of financial expectations at the box office. In 1928, film executive Nicholas Schenck orchestrated a deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) for Keaton’s services. Keaton had little influence over the specifics of the MGM contract; he would relinquish all financial responsibilities for his films, and his salary had already been determined without his input. Despite warnings from Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd about losing his independence, Keaton agreed to sign with MGM due to Schenck’s desire to keep things within the MGM family and his acknowledgment that his independent pictures hadn’t performed well. In hindsight, Keaton regarded this as the worst business decision of his life.

Upon his arrival at the studio, Keaton was greeted by Irving Thalberg, and their initial relationship was characterized by mutual admiration. However, Keaton soon realized that the studio system represented by MGM would severely limit his creative input. MGM operated under strict, pre-planned budgets and schedules, which clashed with Keaton’s preference for simplicity in comedies. He often had to grapple with script-related challenges, and the bureaucracy at MGM made even minor requests a cumbersome process. The creative disparity between Keaton’s independent style and MGM’s structured approach became evident when he received the script for “The Cameraman” (1928).

Keaton trimmed the script significantly, but it was still considerably longer than he believed it should be. He highlighted the simplicity that characterized the best comedies and expressed his desire to work with certain character types. However, MGM operated differently, requiring a meticulous process for even the smallest requisitions.

As MGM transitioned into making talking films, Keaton enthusiastically embraced the new technology and sought to make his next film, “Spite Marriage,” with sound. MGM, however, rejected the idea, preferring to retain the film in silent form to reach theaters worldwide that hadn’t yet adopted sound technology. Additionally, soundstage availability was limited, mostly reserved for dramatic productions. During these early sound films, Keaton and his fellow actors filmed each scene three times: once in English, once in Spanish, and once in either French or German, with actors phonetically memorizing foreign-language scripts and shooting immediately after. Keaton expressed frustration at having to film what he considered poor-quality movies three times.

Keaton persistently tried to persuade MGM to allow him more creative freedom but faced resistance. Irving Thalberg was supportive in certain aspects, permitting Keaton to stage gags and incorporate extended pantomime sequences. Nevertheless, Keaton had to work within the confines of a script, Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath, originally purchased at Lawrence Weingarten’s suggestion, Thalberg’s brother-in-law and Keaton’s producer. In this instance, Keaton retained creative control over the gags and pantomime sequences, and the film was ultimately released as “A Buster Keaton Production” in 1931.

View Buster Keaton’s Promotional Interview for the German Version of “Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath.”

The subsequent project, “Sidewalks of New York” (1932), was not to Keaton’s liking, featuring a millionaire embroiled with a slum-neighborhood girl and a rowdy gang of kids. He found the premise unsuitable and felt uncomfortable with directors Jules White and Zion Myers, who emphasized blunt slapstick. Keaton appealed to Irving Thalberg to relieve him of this assignment but was met with resistance, leading to his reluctant involvement. Surprisingly, “Sidewalks of New York” became Keaton’s biggest box office success, even though he had reservations about it.

MGM introduced Jimmy Durante to replace comical musician Cliff Edwards in Keaton’s films. The contrasting dynamic between the reserved Keaton and the exuberant Durante worked remarkably well, resulting in three highly successful films: “Speak Easily” (1932), “The Passionate Plumber” (1932), and “What! No Beer?” (1933). The latter marked Keaton’s final starring role in his home country. Years later, both Keaton and Durante made cameo appearances in “It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World,” although they didn’t share scenes.

The production of “What! No Beer?” took a toll on Keaton, and he was ultimately fired by MGM after the film’s completion, despite its commercial success. Another account of his dismissal suggests that an altercation with Louis B. Mayer during a party in Keaton’s dressing room, followed by his refusal to attend a publicity event, led to his termination.

Keaton had been considered for a role in the all-star hit “Grand Hotel” but ultimately lost the part to Lionel Barrymore. As “What! No Beer?” neared completion, Keaton pitched an idea to Irving Thalberg for a feature-length parody of “Grand Hotel” with an all-comedy cast. However, the project never materialized.

Despite efforts to revive his career at MGM, including Irving Thalberg’s attempts to salvage their working relationship, Keaton’s starring career in feature films came to an end due to the increasingly strained relationship with the studio and the transition to the sound era.

*P.S: Below is an image of Buster Keaton’s Signature on MGM Studio Document, June 12, 1945. This 1-page document, measuring 8.25 x 10.75 inches, is written on Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer letterhead stationery, featuring a 4-hole punch. Addressed to Buster Keaton, the document details an agreement concerning the film comedian’s two-day unpaid leave. Keaton’s signature appears in the lower left, and the document is countersigned on the right by the Assistant Treasurer for Lowe’s Inc. The image is sourced from Heritage Auctions.

In 1934, Keaton agreed to participate in the production of an independent film titled “Le Roi des Champs-Élysées” in Paris, which ultimately did not see a release in the United States. Today, the film is available and you can watch the full movie here:

Concurrently, he worked on another film, “The Invader,” in England. Despite his efforts, no Hollywood studio was willing to distribute “The Invader.” Eventually, in 1936, the film found its way to American audiences under the title “An Old Spanish Custom,” thanks to a small New York-based film import company.

Upon Keaton’s return to Hollywood in 1934, he embarked on a screen comeback by starring in two-reel comedies produced by Educational Pictures. These shorts primarily relied on visual humor, with Keaton often contributing his own gags, sometimes drawing inspiration from his family’s vaudeville performances and his earlier cinematic works. Keaton enjoyed a significant degree of creative control in staging these films, all within the confines of the studio’s budgetary constraints and using its in-house screenwriters.

The Educational series notably incorporates a greater emphasis on pantomime compared to Keaton’s earlier talkies, and Keaton’s comedic talent shines throughout. Among the highlights of the Educational series is “Grand Slam Opera” (1936), where Keaton not only stars but also crafts the screenplay, portraying an amateur-hour contestant in a humorous narrative.

These Educational films garnered considerable acclaim from both theater proprietors and moviegoers, solidifying Keaton’s status as the studio’s preeminent comedian. However, this came at a premium cost, with Keaton earning a substantial $2,500 per film. In 1937, when Educational faced financial constraints, the company was compelled to economize, leading to the closure of its Hollywood studio. As a result, they could no longer engage Keaton’s services and opted to replace him with Willie Howard, a stage star based in New York.

Following the conclusion of Keaton’s Educational series, he made a comeback at MGM but in a different role, working as a gag writer. He provided comedic material for the last three Marx Brothers films produced by MGM: “At the Circus” (1939), “Go West” (1940), and “The Big Store” (1941). However, these films did not achieve the same level of artistic success as the Marx Brothers’ earlier MGM features.

Additionally, Keaton took on the role of director for three one-reel novelty shorts while at MGM. However, these directorial efforts did not lead to further opportunities for him to helm additional projects.

In 1939, Columbia Pictures enlisted Keaton to star in a series of 10 two-reel comedies, which ran for a span of two years and marked his final starring role in a comedy series. Columbia typically paid its short-subject comedians a fixed fee of $500 per film. However, recognizing Keaton’s exceptional talent, they offered him a more generous arrangement, compensating him at double the standard rate.

The director for most of these comedies was Jules White, known for his penchant for slapstick and farcical humor, resulting in a resemblance to his famous Three Stooges shorts. On occasion, White paired Keaton with a second comedic talent, either the seasoned Monty Collins or the spirited comic dancer Elsie Ames. White, with his unwavering commitment to directing Keaton whenever possible, sometimes to Keaton’s mild vexation, oversaw the majority of these films. Only two of Keaton’s shorts in this series were exceptions, as they were filmed on location outside the studio. These particular films were directed by Del Lord, a former director for Mack Sennett.

Among the Columbia comedies, Keaton held a personal preference for the inaugural entry in the series, “Pest from the West,” directed by Del Lord. This short film served as a condensed and improved remake of Keaton’s 1934 feature “The Invader,” which had received limited attention. Both moviegoers and exhibitors warmly received Keaton’s comedies under the Columbia banner, signifying their popularity and success.

In the 1940s, Buster Keaton’s personal life found stability through his marriage to MGM dancer Eleanor Norris. With this newfound balance, he transitioned away from Columbia Pictures and into the world of feature films. Returning to his role as a daily gag writer at MGM, Keaton contributed comedic material for entertainers like Red Skelton and offered valuable guidance to Lucille Ball.

Keaton took on a variety of character roles in both “A” and “B” feature films during this period. His final starring feature, “El Moderno Barba Azul” (1946), was produced in Mexico and was a low-budget production. Interestingly, this film might not have been widely seen in the United States until its release on VHS in the 1980s, under the title “Boom in the Moon.” Regrettably, “El Moderno Barba Azul” holds a largely negative reputation, with esteemed film historian Kevin Brownlow even labeling it as the worst film ever made.

However, in 1949, critics and producers began to rediscover Keaton’s talent. He received cameo roles in notable films such as “In the Good Old Summertime” (1949), “Sunset Boulevard” (1950), and “Around the World in 80 Days” (1956). In “In the Good Old Summertime,” Keaton assumed the role of director for stars Judy Garland and Van Johnson’s first scene together. This scene featured Keaton’s signature comedic touches, with Johnson repeatedly attempting to apologize to a visibly frustrated Garland, leading to comical hair and dress mishaps.

Keaton also made a memorable appearance in Charlie Chaplin’s “Limelight” (1952), where he participated in a comedy routine involving two inept stage musicians. This routine harkened back to the vaudeville-style humor reminiscent of Keaton’s earlier work. Notably, “Limelight” marked the only time Keaton and Chaplin appeared together on film, excluding the minor publicity film “Seeing Stars” produced in 1922.

In 1949, Ed Wynn, a fellow comedian, extended an invitation to Buster Keaton to join him on his CBS Television comedy-variety show, The Ed Wynn Show. This show was broadcast live on the West Coast, and kinescopes were created to distribute the programs to other parts of the country, as there was no transcontinental coaxial cable until September 1951. The response to Keaton’s appearance was so positive that a local Los Angeles station offered him his own show in 1950, which was also broadcast live.

Titled “Life with Buster Keaton” in 1951, the show aimed to recreate the charm of the first series on film, enabling nationwide broadcasting. The series featured a talented ensemble cast, including Marcia Mae Jones, Iris Adrian, Dick Wessel, Fuzzy Knight, Dub Taylor, Philip Van Zandt, as well as fellow silent-era contemporaries like Harold Goodwin, Hank Mann, and stuntman Harvey Parry. Eleanor, Keaton’s wife, made appearances in the series, most notably as Juliet alongside Keaton’s Romeo in a theater vignette. The theatrical feature film “The Misadventures of Buster Keaton” was later created based on the series. Keaton himself decided to cancel the filmed series because he found it challenging to generate enough fresh material for a weekly show.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Keaton made periodic television appearances, reigniting interest in his silent films. He was sought after by TV shows that wanted to capture the essence of silent-movie comedy. Keaton guest-starred in popular series such as The Ken Murray Show, You Asked for It, The Garry Moore Show, and The Ed Sullivan Show.

Even in his fifties, Keaton effortlessly reenacted his classic routines, including one memorable stunt where he balanced on one foot on a table, swung the second foot up next to it, and held the awkward position midair before a theatrical tumble to the stage floor. Garry Moore remembered Keaton’s unique approach to his falls, acknowledging that it may have hurt physically, but Keaton’s commitment was such that he had to care enough not to care.

Keaton’s films and comedies often revolved around chasing and pursuits, but now, the chase has come to an end. On February 1, 1966, at the age of 70, Buster Keaton passed away in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, a victim of lung cancer. Interestingly, he had been diagnosed with cancer in January 1966, yet he was shielded from the grim prognosis. Keaton believed he was on the path to recovery after grappling with what he thought was a severe case of bronchitis.

During his final days, confined to a hospital, Keaton’s restlessness led him to pace his room incessantly, his heart yearning for the comfort of home. In a British television documentary that celebrated his remarkable career, Eleanor, his wife, disclosed to Thames Television producers that Keaton remained remarkably active. He would rise from his bed, move about, and even partake in card games with friends who came to visit on the day before his passing. His final resting place is at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Hollywood Hills, California.

Buster Keaton was presented with an Academy Honorary Award at the 32nd Academy Awards in 1960. He also has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: one on Hollywood Boulevard for motion pictures and another on Hollywood Boulevard for television.

Six of his films have been included in the National Film Registry, making him one of the most honored filmmakers on that list: “One Week” (1920), “Cops” (1922), “Sherlock Jr.” (1924), “The General” (1926), “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” and “The Cameraman” (both 1928).

In 1957, a film biography titled “The Buster Keaton Story,” starring Donald O’Connor as Keaton, was released. A 1987 documentary, “Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow,” directed by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, won two Emmy Awards.

The International Buster Keaton Society, known as the “Damfinos,” was founded on October 4, 1992, Keaton’s birthday. Its mission is to raise awareness of Keaton’s life and work, with membership spanning various fields in the entertainment industry.

In 1994, caricaturist Al Hirschfeld created a series of silent film star caricatures for the United States Post Office, which included Keaton. Hirschfeld noted that modern film stars were more challenging to depict, while silent film comedians like Laurel and Hardy and Keaton were easier to caricature.

Artist Salvador Dalí, in his essay “Film-arte, film-antiartístico,” praised Keaton’s works as prime examples of “anti-artistic” filmmaking, describing them as “pure poetry.” In 1925, Dalí created a collage titled “The Marriage of Buster Keaton,” featuring Keaton.

Film critic Roger Ebert hailed Buster Keaton as “the greatest of the silent clowns” and acknowledged his courage. Filmmaker Orson Welles proclaimed Keaton as “the greatest of all the clowns in the history of cinema” and a supreme artist.

Mel Brooks credited Keaton as a significant influence on his filmmaking career and as a human being. He acknowledged borrowing ideas from Keaton’s work, such as the changing room scene in “The Cameraman.”

Actor and stunt performer Johnny Knoxville drew inspiration from Keaton for “Jackass” projects. Comedian Richard Lewis considered Keaton his primary inspiration and formed a close friendship with Eleanor, Keaton’s widow.

In 2012, Kino Lorber released “The Ultimate Buster Keaton Collection,” a 14-disc Blu-ray box set featuring 11 of Keaton’s feature films. In 2016, Tony Hale portrayed Keaton in an episode of “Drunk History.”

On June 16, 2018, the International Buster Keaton Society unveiled a four-foot plaque in honor of Keaton and Charles Chaplin, leading to the declaration of “Buster Keaton Day” by the City of Los Angeles.

In 2018, filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich released “The Great Buster: A Celebration,” a documentary about Keaton’s life, career, and legacy. In 2022, two works on Keaton were published, a cultural history titled “Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century” and a biography titled “Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life.”

Finally, in 2023, Keaton’s life and work were the subjects of a graphic novel biography titled “Buster: A Life in Pictures,” authored by Ryan Barnett and illustrated by Matthew Tavares.